I recently wrote a post on Joan Rivers' obscure comedy record "Adam and Eve," which was released on Linden, New Jersey's Sure Records label around 1960-61. I couldn't find a complete or accurate discography for this label, so I created one.

An ongoing source of confusion about Sure Records is that two labels by that name existed less than 100 miles from each other. The Sure Records at 20 East Elizabeth Ave. in Linden, New Jersey, operated in care of G&S Productions, and George Stalter—presumably the G and/or S of G&S Productions—arranged, conducted, and/or co-wrote many of the label's releases. Many of the songs on the label were published by Candasa Music. An hour and a half away in Broomall, Pennsylvania, a different Sure Records was run by Leonard "Len" Rosen's Sure Music and Record Company. Rosen also ran Cedargrove Records. I'm going to refer to the two labels henceforth as NJ Sure and PA Sure.

Rosen's PA Sure label released the Virtues' 1959 hit "Guitar Boogie Shuffle" and a number of Mummers Parade recordings by string bands such as the Aqua String Band. The label was active through the 1960s; Billboard reported in 1967 that this Sure was starting to market 7-inch LPs for jukeboxes.

Stalter's NJ Sure label issued a handful of pop recordings by Bobby Valo, Julie Stevens, the Hollywood Playboys, and the Fascinations, and appears to have ended its run circa 1960-61 with the Joan Rivers record.

How can we be sure that these were two different labels? It's certainly bizarre that two labels named Sure existed so close to each other, but they had different addresses, different label designs, different artists, and different distributors. (The NJ Sure was distributed by Adonis Records, and some of the PA Sure records were distributed by Mercury Records.) The two labels issued releases concurrently, and their catalog numbers don't line up with each other.

NJ Sure used a plain blue label after its first release, which had a black label, and the logo changed from cursive to block letters after a few releases. The PA Sure labels often pictured a rocket or an archery target and came in many colors.

Billboard listed NJ Sure as a new label in its May 18, 1959 issue, but the label had existed since 1957, when it released the Golden Bells' "Bells Are Ringing." Billboard itself had reviewed NJ Sure's Bobby Valo single three months earlier in its February 9, 1959 issue.

The PA Sure label was incorporated on March 5, 1959. Its principle place of business was registered as Philadelphia, but many of its records bore a Broomall address. Also in 1959, Rosen incorporated Sure Music Talent, Inc., at his Broomall address. This company booked string bands for the Mummers Parade.

I can only guess why these two labels tolerated having another label in the area that went by the same name. NJ Sure existed first and released one single in 1957, but it doesn't seem to have done anything else until nearly two years later, which was the same year that PA Sure was incorporated. When NJ Sure reactivated with its Bobby Valo single, George Stalter was heavily involved, but he doesn't appear to have been involved in the Golden Bells record from 1957. Even though the address on the label of the Golden Bells record is 20 East Elizabeth Ave. in Linden—the same as G&S Productions—I'm guessing that this single was not issued by George Stalter. Maybe Stalter took over that location and label in 1958 or early 1959?

S-1001/1002 The Golden Bells – "Bells Are Ringing" b/w "Pretty Girl"

The blog Doo-Wop has a post on the Golden Bells. You can listen to "Bells Are Ringing" here. Jerry Osborne's 1998 book The Official Guide to the Money Records valued this single at $1,500.

S-103 Bobby Valo – "Hey Lover Girl" b/w "With All the Love I Have"

Notice that the catalog numbers went from S-1001/S-1002 to S-103. These songs, like many songs on Sure NJ, were published by Candasa Music and were co-written by George Stalter. Stalter co-wrote "Hey Lover Girl" with someone named Gottfried. It might have been Joe Gottfried of New York's Adonis Records, which was NJ Sure's distributor. Billboard spelled his name variously as Gottfried and Gotterfried. The ASCAP database has no record of any George Stalter songs.

|

| Billboard's February 9, 1959 review |

S-104 Julie Stevens – "Don't Worry About Me" b/w "Please Forgive, Please Forget"

Stevens' single was released about a year after Valo's. The publisher of the A side, Mills Music, ran an ad for the single in Billboard's March 7, 1960 issue. That might be why Billboard reviewed the single the following month! Mills Music was a huge ASCAP firm that represented famous songwriters such as Duke Ellington, Hoagy Carmichael, and Leroy Anderson.

|

| Billboard's April 11, 1960 review |

|

| Mills Music's Billboard ad from March 7, 1960 |

S-105 The Hollywood Playboys – "Ding, Dong, School Is Out" b/w "Talk to Audrey"

This record saw some regional

action. The A side reached the Top 15 at WNDR in Syracuse and received

some airplay at KFXM in San Bernadino, California. The blog White Doo-Wop Collector has a post about the Hollywood Playboys that includes some great photos. You can listen to "Ding, Dong, School Is Out" on YouTube.

S-106 Fascinations – "Midnight" b/w "Doom Bada Doom"

This

white doo-wop tune might be Sure Records' best-remembered release. The

Fascinations' lead singer was Jordan Zankoff from West Akron, Ohio.

After one record with the Fascinations, he moved to New York and

performed in the Boulevards and Jordan & the Fascinations under the

name Jordan Christopher. Several videos of the song can be found on YouTube. An article about Zankoff from the Akron Beacon Journal can be found here, although it mixes up NJ Sure and PA Sure. Both of these Sure sides were included on a bootleg anthology of Zankoff's groups.

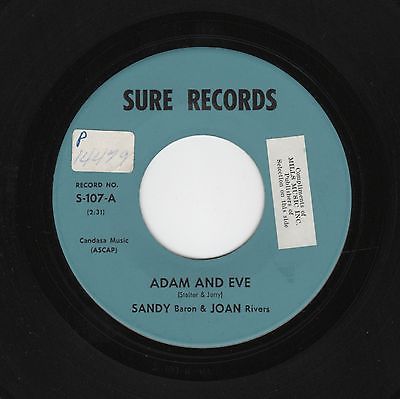

S-107 Sandy Baron & Joan Rivers – "Adam and Eve" b/w "Little Mozart"

Music Weird has a whole post about this record here. Around this time (1961),

Baron also appeared on the Sickniks' "Wadja Say, Mr. K? II" on Amy

Records, a parody of a Russian press conference, which charted in Syracuse

and Philadelphia.

S-108 Frank Perry – "Wid-I-Zen" b/w "Far from You"

You can listen to this record over at the

Giant Mines blog. "Wid-I-Zen" is a novelty song based on a word game in which the nonsense syllables "idiz" are inserted into the middle of words. For example, the word

hoot becomes

hidizoot. It's similar to the

dizouble dizutch stuff heard in Frankie Smith's "

Double Dutch Bus." The B-side is a standard pop vocal number.

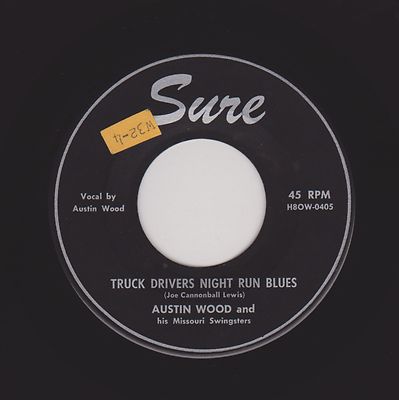

Sure Records of Missouri and Tennessee

Adding to the Sure Records confusion is this Missouri label that released a couple of rockabilly singles by Austin Wood in 1957-1959. These labels have the same logo as the NJ Sure. This must have been a standard font that pressing plants used.

And a Sure Records in Jackson, Tennessee, released a record by Wayne Williams in 1958 that had almost the same catalog number as the first release on NJ Sure: 1001.

Adonis Records

Adonis Records distributed Sure Records. Adonis was a New York label run by Joe Gottfried (or Gotterfried), Ivan Ellis, and Sylvan Epstine. Some of the label's artists included the Four Coachmen, Jean Martin, Frank Simone, Johnny Saber, and Wayne & Ray. The label also had a children's imprint called Peekaboo Records and distributed the Tommy Heck Quintet's "The Lost World" on Chariot.