|

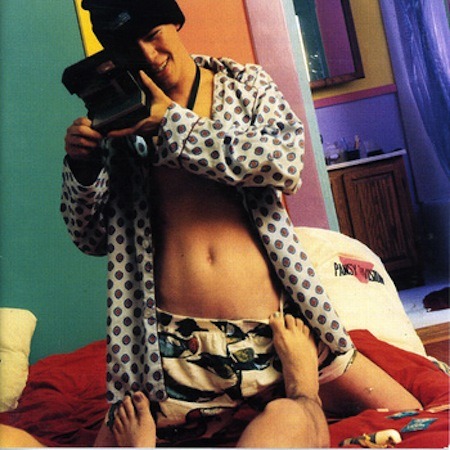

| Jon Ginoli in yellow. Photo by Lauren Bilanko. |

The poet Edmund Miller, who wrote the books The Go-Go Boy Sonnets: Men of the New York Club Scene and Fucking Animals: A Book of Poems, told me that he liked Pansy Division because you could understand their lyrics. I suspect that he also liked what their lyrics were about.

Pansy Division, like Miller, put themselves out there as openly and defiantly queer artists, whatever the personal and professional risks, at a time when the outcome was unpredictable, to say the least. Miller, an academician, published the homoerotic Fucking Animals in 1973, and Pansy Division debuted with "Fem in a Black Leather Jacket" on Lookout! Records in 1992.

What the Buzzcocks's Pete Shelley—and, to a lesser extent, Morrissey—had previously suggested in lyrics, Pansy Division's Jon Ginoli made explicit. Really explicit. Pansy Division didn't just sing about being queer; they sang about queer sex, in detail.

I bought all of the early Pansy Division singles as they were released. As a straight, Midwestern guy who missed out on punk's first wave, I recognized queercore and riot grrl punk as the real deal: These bands were way more punk than Green Day or NOFX. They were dangerous! They fought for tangible causes that affected people's daily lives, and in Pansy Division's case, it was easy to imagine the band getting hauled in on obscenity charges for their explicit lyrics and picture sleeves.

But beyond their rebelliousness, Pansy Division was fun. I caught them live twice, and they put on a great show, rocking out with their hilarious, sing-along anthems and spraying the audience with Silly String.

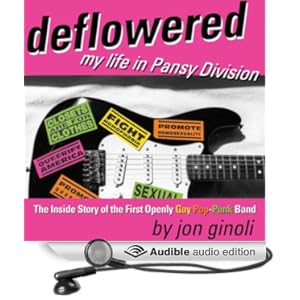

The band is still active. Their catalog is available on Bandcamp, and last year Ginoli released an audio book of his 2009 memoir, Deflowered: My Life in Pansy Division.

Music Weird talked to Pansy Division's lead singer and songwriter, Jon Ginoli, on June 1, 2014.

After the 2 Live Crew obscenity debacle, it seemed like Pansy Division could get arrested for peddling smut. What kind of troubles, if any, did you run into from authorities or moral crusades or whatever?

We had a few problems, but not too many. I can think of three things:

1. When our first album came out, which had a nude guy on the cover, the place our label used to manufacture its cassettes, in Alabama, refused to print it.

2. In Jupiter, Florida, a complaint was made against a record store over our "Bill & Ted's Homosexual Adventure" 45 because the sleeve was "obscene"—it had a blurry picture of two guys blowing each other. They were forced to keep the record behind the counter. It made all three local stations' newscasts that day. I had a VHS tape of the coverage but it decayed over time. Pretty ridiculous.

3. Any covers that displayed any male genitalia had to have the shrinkwrap whited out by hand before being shipped to Japan.

Pansy Division seemed like a "high concept" band from the beginning: you had a vision for creating an openly queer punk band with sexually frank lyrics. Did you ever come to feel that the concept was confining or restrictive?

It didn't feel restrictive. Back then I felt like we had the field to ourselves. It felt infinite. Over time we got more introspective, because otherwise you do repeat yourself. I always thought even our raciest stuff was sincere, not done for shock value. It was done for people who we thought would get it. If other people thought we were rubbing it in their faces, boo hoo. We grew up with heterosexual images rammed down our throats; we felt we were there for others who felt that way, be they queer or not.

I saw you play live twice in Indiana, and you were well received both times. Did you have any bad or intolerant concert experiences?

The shows we did opening for Green Day were really the only times we received negative reactions, and even so, it was usually pretty mixed. I remember on the first Green Day tour, we played a venue in Indianapolis that was way too small for them to be playing; they'd gotten big quite suddenly that summer. To reach the dressing room and get to our van, we had to be escorted through the overpacked club by big security guards. Some young guy yelled at us, "Fucking faggots!" I yelled back, "We're not fucking faggots, we're buttfucking faggots."

We were pretty nervous when we set out for our first tour, but nothing happened. Nothing ever really did at our own shows, which to me signaled that conditions for gay people had improved. We never got picketed or anything like that.

|

| Wish I'd Taken Pictures album cover |

Did you feel a kinship with the lesbian riot grrrl bands, like CWA and Tribe 8? Did you ever play with any of them?

Yes and yes. I loved both of those bands. It's a shame CWA didn't stick around long enough to make an album; they released only two songs, both on compilations, both of which we were on too. I tried tracking them down a few years ago and failed. Even Kill Rock Stars, the label one of the comps was on, had lost touch with them too. We brought CWA down to San Francisco to open for us once at a gay pride weekend show we did in SF, in 1992 I think, and we played with them once in Olympia.

We played with Tribe 8 a bunch of times. The second Pansy Division show in San Francisco—when I didn't really have a band yet and was doing Pansy Division as a solo project for a few months—was opening for them. We both began at the same time. Chris from Pansy Division and Lynn Breedlove from Tribe 8 even knew each other, but didn't know the other one was playing in a queer band until we were on the same bill one night!

I think Tribe 8 were like the Black Flag to our Ramones, or the Rolling Stones to our Beatles. We were confrontational, but friendly. Tribe 8 pushed people's buttons way harder. They were an amazing live act.

You must have heard from a lot of fans who said that Pansy Division changed their lives or gave them courage to be themselves.

It's one of the most rewarding things about doing this band. I've heard it a lot. People don't recognize me very often, but if I get introduced to people nowadays, I hear a lot of that. We started the band hoping that kids would hear us; it was what we needed to hear when we were teens. The fact that it did get through to people is still very gratifying for us to hear.

On a related note, I ran into Marcus Ewert yesterday; he was a cover model for our Deflowered and Wish I'd Taken Pictures albums. He told me that he didn't get that much feedback from being on our covers back in the '90s. But in the age of the internet, many people have contacted him saying they'd kept our album covers under their beds and would use those pictures as jerk-off material. He loves hearing stories like that, and so do we.

Nowadays, when the subject of our band is introduced, it seems people either love it or hadn't heard of it. It's fairly all or nothing. However, the under 30s are almost uniformly unfamiliar with our band. Word of mouth about us traveled a long way, but it had its limits.

No comments:

Post a Comment